A Storm to Remember:

Hurricane Harvey and the Texas EconomyEconomic Impact

The extent and cost of Harvey’s destruction were significant. But when balanced against the anticipated increase in business activity due to reconstruction and restoration efforts, combined with an influx of funding from federal aid and insurance payments, the effect on the state’s economy may be much less severe than many expected.

Gains from increased construction activity and associated spending undertaken to repair and rebuild should help offset losses in the months and years to come.

During and immediately following the storm, Texas communities in the affected areas faced costs associated with emergency response, evacuee shelters, debris removal and infrastructure repair. Many suffered damage to public buildings and vehicles that must be repaired or replaced. Many businesses, in addition to repairing damaged facilities, must replace some or all of their equipment and inventory.

Meanwhile, thousands of evacuees staying in hotels or rental units faced temporary housing costs and, upon returning to their flood-damaged homes, began replacing floors and sheetrock and purchasing furniture, household goods, electronics, clothes and vehicles.

Harvey disrupted a broad range of industries, but manufacturers represented a large share of them.18 Although many were back in operation within five or so days, some experienced significant disruptions for two weeks or more.19

Based on information submitted to the Comptroller’s office, federal, state and local governments, along with private insurers, had spent or committed about $31 billion for Harvey-related disaster relief and rebuilding as of Nov. 30, 2017. This number is likely to rise. Money for reconstruction efforts will come primarily from the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), state and local governments and private insurance (Exhibit 2).

Exhibit 2: Funding Sources for Hurricane Disaster Relief

- Federal Emergency Management Agency

- National Flood Insurance Program: payments for flood claims

- Individual assistance: payments to individuals and households

- Public assistance: reimbursements to state and local governments and certain nonprofits

- Small Business Administration

- Home loans

- Business loans

- U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development – Community Development Block Grants

- State and Local Funds

- Private Insurance Companies

- Nonprofit Organizations

Sources: Congressional Research Service and the Texas Legislative Budget Board

All of this spending will spur economic growth.

Without the boost from rebuilding, Texas’ gross state product (GSP) would have required four years to recover to pre-Harvey expectations; personal income would require five years. Single-family residential housing stock would take seven years to rebound to normally expected levels, while non-residential building stock in the affected areas would require four years for recovery.20 With the help of federal, state and local government aid, however, all of these measures should recover in the second year after the storm, and Texas should gain about half as many jobs as it would have lost in the absence of government aid.

Exhibit 3 displays the estimated indirect losses and gains to Texas GSP resulting from Hurricane Harvey. In all, the total estimated net impact (losses plus gains) is a $3.8 billion loss in GSP in the first year following the storm. (To put this loss in perspective, Texas’ GSP was $1.6 trillion in 2016.)21

Recovery will stimulate economic activity, producing an estimated $800 million cumulative gain in GSP over three years.22

Exhibit 3: Net Economic Impact of Hurricane Harvey on Texas Gross State Product(in billions of dollars)

| Impact | Year 1 | Year 2 | Year 3 | Years 1-3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimated Losses | ($16.8) | ($2.0) | ($1.0) | ($19.8) |

| Estimated Gains | $13.0 | $4.1 | $3.5 | $20.6 |

| Net Economic Impact | ($3.8) | $2.1 | $2.5 | $0.8 |

Source: Texas Comptroller of Public Accounts

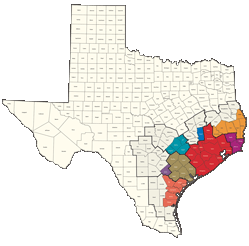

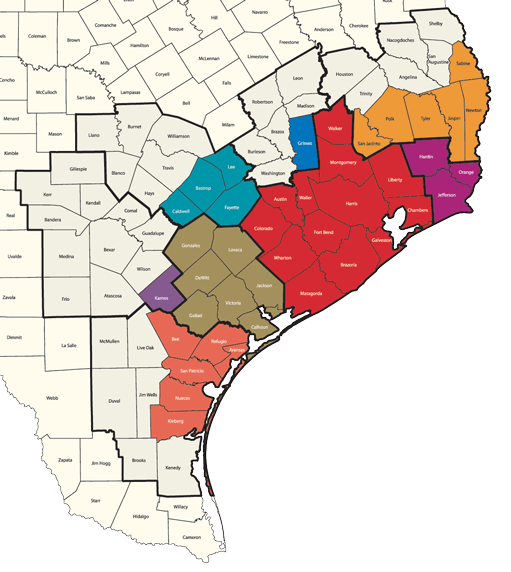

It’s also possible to assess economic costs on a local basis by examining the counties included in Texas’ councils of government (COGs), multi-county regional planning bodies. Harvey affected eight COG regions — the Houston-Galveston, South East Texas, Golden Crescent, Coastal Bend, Brazos Valley, Deep East Texas, Capital and Alamo areas — and 41 counties within them were designated as disaster areas (Exhibit 4).

The storm hit the 13-county Houston-Galveston COG region hardest, causing an estimated $16 billion economic loss during the first year. FEMA designated all 13 counties in this region as disaster areas. The Coastal Bend, South East Texas and Golden Crescent COGs can expect first-year losses projected at $350 million to $800 million each. The Alamo Area, Capital Area and North Central Texas regions, by contrast, stand to gain in Harvey’s wake, each with an estimated $1 billion to $2 billion in additional economic activity.

Exhibit 4: Texas Counties Affected by Hurricane Harvey

Source: Federal Emergency Management Agency

Counties declared by FEMA as disaster areas and boundaries showing the eight councils of governments (COGs) affected.

DETCOG

Deep East Texas Council of Governments

Jasper, Newton, Polk, Tyler, Sabine, San Jacinto

SETRPC

South East Texas Regional Planning Commission

Hardin, Jefferson, Orange

H-GAC

Houston-Galveston Area Council

Austin, Brazoria, Chambers, Colorado, Fort Bend, Galveston, Harris, Liberty, Matagorda, Montgomery, Walker, Waller, Wharton

BVCOG

Brazos Valley Council of Governments

Grimes

CAPCOG

Capital Area Council of Governments

Bastrop, Caldwell, Fayette, Lee

GCRPC

Golden Crescent Regional Planning Commission

Calhoun, DeWitt, Goliad, Gonzales, Jackson, Lavaca, Victoria

AACOG

Alamo Area Council of Governments

Karnes

CBCOG

Coastal Bend Council of Governments

Aransas, Bee, Kleberg, Nueces, Refugio, San Patricio

Our estimate of first-year effects on real GSP by sector shows the hardest-hit industries include memberships (to clubs, sports centers, parks, theaters and museums), telecommunication services and entertainment, while those faring the best include health services, food and beverages and, for obvious reasons, rental housing, motor vehicles, furniture and clothing.

The auto industry in particular should see increased demand as consumers seek to replace the cars and trucks damaged or destroyed by flooding. Although this increase in demand is expected to spike during the first year after the storm, it should return to pre-Harvey levels within five years.

As expected, the Texas economy as a whole appears to have bounced back to pre-Harvey levels as of the end of the fourth quarter of 2017.23

Data and Assumptions

For this analysis, Comptroller economists used a Regional Economic Models Inc. (REMI) model based on Texas’ 24 COG regions to examine economic activity. Eight of the 24 include the 41 counties that bore the brunt of the damage inflicted by Harvey, as determined by FEMA’s disaster designation.

The methodology used to estimate losses and gains in economic activity as a result of Harvey relied on a combination of data, assumptions and estimates. REMI calculates the effect of losses and gains on projected GSP for the duration of the time period used in this analysis. (Appendix 2 provides a detailed description of the methodology used in this analysis.)

Several factors influenced the inputs used to generate this estimate, including the number and population of counties affected by Hurricane Harvey as well as the extent and duration of the damage.

Because the affected areas do not match up neatly with COG boundary lines, this estimate assumes only the affected counties experienced productivity loss and reduces nonfarm productivity by the proportion of people in affected counties to the total population of each region.

Our estimate also addresses reconstruction and repairs in the first three years, although no actual timeline for reconstruction has been determined.

The estimate also assumes the duration of business closures or reduced revenue as follows:

- medical care facilities: four days

- manufacturing and oil- and gas-related production: two weeks

- all other industries: one week

Recovery and Beyond

Despite the transitory nature of Harvey’s impact on employment and business activity, the damage to property and infrastructure has been severe. Moreover, insured losses are expected to be a smaller share of the total damages compared with other major U.S. hurricanes because a larger-than-usual share of the property damage was caused by flooding rather than wind damage, and flooding generally is not covered under homeowner policies.

The negative economic impact of lost productivity and damage to structures, however, is expected to be counterbalanced largely by businesses’ quick recovery as well as the money communities and businesses spend to rebuild.

Texas’ diverse and resilient economy will help buoy the state from Harvey’s impact. While some industries continue to struggle, most businesses are recovering and moving ahead. In all, our analysis indicates that Hurricane Harvey will have minimal long-term effects on the Texas economy, which — with time — will recover and be stronger than ever.

Hurricane Harvey and the State Budget

The damages wrought by Harvey will affect the state budget as well. While the federal government, local authorities and private insurance are providing much of the funding needed for cleanup and rebuilding, the state may have further expenses.

Determining funding sources and storm-related expenses is an ongoing task, and the picture is changing rapidly as information is shared among state, federal and local entities. The Comptroller, Legislative Budget Board and the Governor’s office are working together to identify and track Harvey-related revenues and expenditures.